From anxiety to depression to neuroinflammatory processes we return to the role of well-being molecules with the metabolism of tryptophane

We have already had the opportunity to clarify how a good endogenous production of serotonin is essential for our mental health, since it is able to make us feel good, balanced and serene. We have also said that the main source of serotonin is an amino acid called tryptophan and to understand how the body “uses” tryptophan to obtain serotonin, let’s talk about tryptophan metabolism.

The synthesis of serotonin takes place in two distant areas of the body: the intestine (enteric nervous system) and the brain (central nervous system), and which take care of it are specialized cells, not surprisingly called serotonergic cells. This complex mechanism of metabolic synthesis takes place within an even more sophisticated bidirectional system called the brain-intestine axis, in which the dialogue between the two extremes is ensured by a dense neuronal network. In the intestine, specific cells called enterochromaffins are responsible for this operation, while in the cerebrospinal area this function is performed by cells that make up the so-called raphe nuclei.

Tryptophan reaches the digestive system from food, in particular from some common foods that are naturally rich in it and that we should consume – alternating them – every day, including:

- Cocoa/dark chocolate

- Salmon

- Nuts and oilseeds

- Egg

- Dairy products

- Tuna

- Poultry, especially turkey

- Pineapple

- Tofu

- Nutmeg

Once these foods arrive in the small intestine to be broken down into their basic components, the amino acid tryptophan is finally “isolated” and assimilated only at the end of a complex metabolic process. Not always, in fact, all the tryptophan we ingest can be completely metabolised. It may happen that, for example, the concomitant consumption of other amino acids or carbohydrates can limit or hinder their absorption. For this reason we must be sure to include many foods rich in this amino acid in our diet, considering that a part is always and in any case “lost” in some passage. In the best case, once released into the peripheral circulation, a high percentage of tryptophan binds to albumin (a protein synthesized by the liver), while the other is available in free form. However, let’s get into the description of this important process of biochemical synthesis a little better.

While it is true that two “end products” of tryptophan metabolism are the neurotransmitters serotonin and melatonin, numerous steps take place in the middle of this pathway which lead to the production of another “median” substance called kynurenine. As easily understood, as much as 90% of serotonin synthesis takes place in the intestinal tract, where tryptophan also acts as a protector of the mucous membranes. Only 10% of the entire process takes place in the brain, involving the amygdala.

So let’s see a simplified and tripartite scheme of tryptophan metabolism in balanced and healthy conditions:

A part of the TRP is used for the production of proteins (let’s remember that we are talking about an essential amino acid), the “building blocks” of our body

Another substantial part of this substance is instead used by the body for the synthesis of kynurenine from which kynurenic acid and NAD (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide, an important antioxidant involved in the cellular energy production process), and/or quinolinic acid are obtained , a substance which, as we will see later, on the contrary is not really our friend. In this specific process, TDO/INO enzymes are used

Finally, a variable percentage between 1 and 10% is involved in the synthesis of serotonin and melatonin.

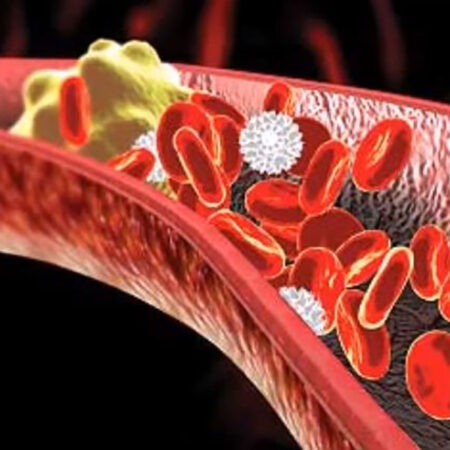

When sufficient quantities of tryptophan enter the body, and this is used in the correct way, the synthesis of serotonin takes place in a regular way and this neurotransmitter acts as a promoter in the processes of processing emotions, in learning and in memory, especially in the limbic area of the brain. If, however, imbalances occur in some step of the process, with an imbalance “in favor” of the synthesis of kynurenine and quinolinic acid, the consequence is a deficit in the production of serotonin, with cascading symptoms ranging from mental of mood to processes of sub-inflammation affecting the intestinal mucous membranes. In fact, if we consider the two nervous systems – the enteric and the central one – as a whole and not as two watertight compartments, it is clear that if we have an imbalance on one side, the other will also be negatively affected.

Quinolinic acid and the link with neuroinflammation

Let us return for a moment to the metabolic process of dietary tryptophan and the production of quinolinic acid via kynurenine. Even if this step is of little interest to us, it actually represents the most substantial part of the entire tryptophan reconversion mechanism.

What is quinolinic acid? A neurotoxic substance which, if present in the body in higher than normal quantities, induces states of inflammation in the nerves and brain and inhibits the production of serotonin and melatonin. Understandably, both of these consequences, being intimately linked to each other, lead to conditions of mental discomfort, mood alteration and sleep-wake rhythm.

Therefore, also an altered metabolism of tryptophan and an excessive quantity of circulating quinolinic acid are among the risk factors of depressive and anxious states, and of common neurocognitive disorders including memory deficits and migraine, which could be improved taking into account this anomaly of metabolism .

Quinolinic acid therefore has pro-inflammatory effects, it acts by lowering the immune defenses and increasing the oxidative stress of the cells. The metabolic process of breaking down dietary tryptophan is therefore a delicate mechanism, which involves various actors – enzymes, above all – which takes place in different organs of the body, and which above all leads to the synthesis of substances which act in differently positive ways on our body.

What we recommend to do in the presence of anxiety, depression and sleep-wake cycle problems

To gain insight into your gut-brain axis and tryptophan metabolism in your gut, we recommend having an organic acid analysis through a urine sample. This type of test provides information on the nutritional and metabolic profile, allowing the doctor or specialist to evaluate if you have sufficient levels of serotonin for your needs and if you may be suffering from a state of chronic sub-inflammation due to a metabolism of tryptophan altered.

Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8000752/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6158605/https://academic.oup.com/advances/article/11/3/709/5673193?login=false

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00123/fullhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7290275/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2019.00158/fullhttps://www.biovis.eu/wp-content/uploads/Biovis_Tryptophanstoffwechsel_2018_WEB_IT.pdf

- https://www.stateofmind.it/2021/04/triptofano-disturbi-psichiatrici/https://www.nonsprecare.it/serotonina-come-aumentare-ormone-della-felicita